For those family genealogists out there, the term “brick wall” has a certain meaning. It is when all the clues run out and those exciting new discoveries come slowly or not at all. Well those “brick walls” can also pop up in the study of general history when we can’t find answers to our questions about a subject or topic.

I recently received a question about a family of coopers who were part of Port Byron’s very active barrel manufacturing business. (A cooper is one who manufactures barrels.) And I had to say that what we don’t know far outweighs what we do know. Most of what is known comes from a short description in the Brigham’s 1863 County Directory, where a short sentence says that the cooperage was in a two-hundred-foot-long stone building and that it supplied barrels to the large mill of John Beach. It has been written that the Beach mill could turn out 500 barrels of flour in one day, so it is no surprise that coopers were in high demand. It was also noted that the cooperage employed about 50 men. (Barrels were the cardboard box of the day. They were watertight and used for the storage of wet and dry products. With their round shape, they were easy to handle by simply rolling them along ramps or on the floor.)

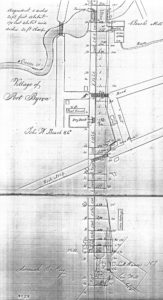

A few more clues were found in an 1834 Erie Canal survey that noted the location of the cooperage. A couple notes about this survey map- It shows the canal running straight down the middle of the page. West is to the bottom and east is at the top. This is how surveys were done. And the map shows lock 7, which was the seventh lock west of Rome. This would later be renumbered as lock 60.

Lock 7 can be seen at the bottom of the page and next to it was a saw mill. This water-powered mill used the flowing water of the canal lock by-pass to turn the machinery. Above the lock and mill is a long rectangular building with the note “stone cooperage.” Beach’s Mill can be seen at the top of the page next to the Owasco Outlet.

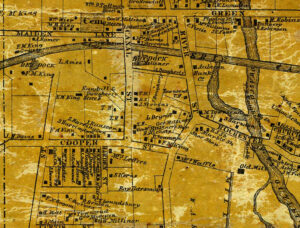

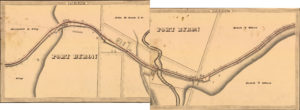

Here is the 1834 map that was made from the survey. Now west is to the left and east is to the right. Lock 7, the saw mill and cooperage can be seen above the words PORT BYRON. Beach’s Mill can be seen where the two pages were put together. Note that the cooperage is not labeled on the final map.

This map was from the 1850s enlargement of the canal. The newly doubled lock 52 can be seen left of center as can the old lock 7(60) just below it. To the right you can see a long rectangle that notes the footprint of the cooperage.

Our last clue is from the 1859 map where we find Cooper Street, what is today’s Rochester Street west the Outlet. Note the location of the “old mill” which was the Beach Mill. But all traces of the old canal have been erased, as with the cooperage.

So it is clear that the cooperage was a large business. The 1850 census notes that there were 27 men who were coopers, but these were likely the last of the industry as by 1850 there is no mention of the cooperage in any history. Our family of coopers, who prompted this question, were part of the 27 in 1850 but had moved by 1855.

As happens so many times with local history, the description of the business that was printed in 1863 was repeated word for word in later historical accounts. Even the local paper, normally a wealth of local information, never mentions the seemingly long forgotten business. An article about a house fire in 1914 notes that Samuel Dougherty was the foreman of the Beach Cooperage, but that is it. His son, Henry Dougherty of mincemeat fame, operated another cooperage later in the 1800s, maybe suggesting that he or his father had carried on the business in some fashion. The Dougherty cooperage was located on the west bank of the Outlet between what is today Rochester Street and Moore Place.

John Beach’s mill, once called the largest in the state, is also another of our “brick walls,” for it predated photography and no one cared to make a drawing of it. So again, all we have are the often repeated historical descriptions of a business that saw it’s prime days in the 1830s. The mill burned in 1857 leaving no trace aside from the two-mile-long mill race that was later used to supply water to the canal. I have written about this mill and John Beach in previous posts.