In October 1873, Colonel William Jones assembled his forces. The men built two forts that they named Fort Armstrong and Fort Graham to honor their leaders. These log and earthen fortifications looked out over the landscape from where the expected attack would advance. In addition to their sidearms, a ten-pound-canon was mounted, and a 24-hour-guard was established. These citizen soldiers were farmers who had made the short walk from their nearby homes and they stood ready to repel the opposing army. For war had come to Mentz.

Well. Okay, to be honest, the “war” was more a spat, a dust-up, or a standoff between local landowners and the New York Central Railroad. But for the national, and even the local news, it was all worthy of the banner that read; “The Port Byron Railroad War.”

To set the stage for this war, we need to look back to 1853 and the merger of a number of smaller railroad companies into the New York Central. One of the early projects taken up by the new company was to construct a direct connection between Rochester and Syracuse. Before this, a traveler wishing to go between the two cities had to travel in a circuitous route that took them south to Auburn and then back north to Rochester. A major issue for the direct route was that it needed to cross the deep, wet muck of the Cayuga Marshes, a seemingly insurmountable engineering problem. The task was taken up by Van Richmond, who was a canal engineer. Richmond had overseen the construction of the Seneca River Aqueduct of the Enlarged Erie at Montezuma. Although the aqueduct was built with driven piles, Richmond surmised that he could built a mattress of brush and logs and place the railroad embankment on top of that to “float” the tracks over the wetlands. He was so sure of his idea that he promised his life savings that it would work, and it did. This line, still is use today, became known as Water-Level Route between New York City and Buffalo.

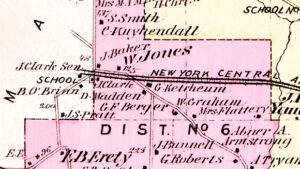

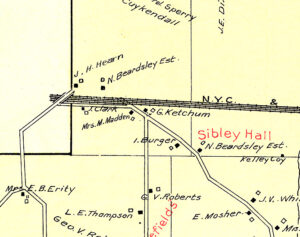

Also in the 1850s, the company had been given the authority by the state to take a strip of land 6-rods, or about 96 feet in width across what land they needed to build the line. This was enough land to lay down two sets of tracks. As the train traffic grew along this line, the company decided to expand to four tracks and the state gave them the authority to take another two rods or 32 feet of land. This would allow for high-speed express traffic on the inner two tracks and slower local service on the two outside tracks. The land acquisition process involved agents from the NY Central coming to town, telling the landowners what they were taking and what they would be paid for their land. It was a government sanctioned form of privately funded Eminent Domain. But simple payments was not enough for some landowners whose land was split by the railroad. Abner Armstrong, William Jones, Lany Graham and Andrew Myer, all who lived along the railroad in the High Bridge area, asked for a bridge over the over the busy tracks where more than a hundred trains a day could go thundering past at high speeds. The railroad was not agreeable to building a bridge.

If you look at the old maps, you see that the construction of the railroad created an odd intersection at “High Bridge.” The new railroad cut through what we call today Berger Road and also the road that ran from Montezuma to Howland Island. And it is safe to say that a bridge had been constructed where the tracks passed through a cut in the landscape. This left an “at-grade” crossing a few hundred yards east of the bridge. For those on the north side of the tracks, they had to cross the tracks to go to Port Byron. And the papers are filled with reports of accidents and deaths were someone crossing the tracks were hit by a fast moving train.

So when the railroad construction crews reached the High Bridge area of northern Mentz, they ran into some resistance. The local men, under the direction of William Jones, who had been given the title of Colonel in 1863 when he was appointed as an officer of the Cayuga County National Guard, had begun preparing to defend their land by building their forts. The number of “soldiers” varies by report, but it appears that 60 to 100 men pitched their tents, created the earthwork and log fortifications, put up the American flag and were armed. Thus began the “Port Byron Railroad War.”

It is clear that at first the NY Central responded in force. A letter to the Editor of the newspaper stated that the railroad workers were armed with; “guns, clubs, stones, shovels, spades, pickaxes and more.” A book about the history of the NY Central titled; “Men and Iron,” notes that Superintendent Burrows of the railroad who was a “forceful citizen” and lacking in “anything that faintly resembled tact,” had sent a train of armed employees to the site and ordered them to charge the forts. The employees resisted and were fired, and little fighting occurred.

But the idea of the NY Central sending an armed train to take on the local men was fodder for the papers, and they of course, immediately took sides. The Auburn paper, which was more sympathetic to the railroad, noted that the leaders were ridiculously marshaling the excited men who brandished their rusty muskets. The Buffalo Evening Courier was a bit more sympathetic to the men stating that they should be congratulated for standing up for their rights and that the they were entitled to the thanks of the community. The article also noted that the men had built a cabin on the land and installed a guard and his family, The 1938 book, Men and Iron, noted that a local clergyman came to the battlefield and blessed the men, comparing them to the minute-men of 1775 and telling them that they were fighting a holy war. It doesn’t appear that there were any injuries and the local law enforcement was called in to restore the peace. The railroad decided to squeeze the extra two tracks onto their existing land and let the case be settled in the courts.

At first, all four men were part of the trial and had to be represented. This required all the men to travel as the courts and the railroad moved the location of the trial from Auburn to Geneva to Canandaigua. So it was decided to let Abner Armstrong fight the good fight and that all would abide by whatever the outcome was, be it against or for them. The case went on for over a year and in the end, the men got the money they wanted, but no bridge, and the railroad got the land they needed. But, it is clear that someone rerouted the road to the south side of the tracks, thus eliminating the at grade crossing. The bit of the old Berger Road north of the tracks became the dead-end Updyke Road. This explains the odd angle of the now closed bridge.

Soon after, in 1878, the Evening Auburian carried the news that Colonel William Jones and his son John, and William Graham and his son Zack, had left for Texas to try their hand in the cattle business. The paper noted that this act marked the end of the saga known as the “Port Byron Railroad War.” However, the life of the cattleman was not to last as a 1879 paper carried the news that the Jones and Graham families had returned to Port Byron.