Port Byron’s Water Supply Through the Years; Drinking Auburn’s Sewage.

Water Supply of Port Byron Grossly Contaminated, State Report Says, Blaming Auburn. This was the headline in the September 9, 1915 Auburn Advertiser-Journal, and it stated what everyone already knew. Every water source in the village was contaminated with sewage and had been for a number of years. What it couldn’t tell the reader was that it would remain that way for many more years.

There are two main principals in this story, Auburn and Port Byron, and in each case, the issue can be broken down between water for human consumption and industrial manufacturing, and sewage wastes. “Sewage” is a broad term that includes runoff from city streets, human feces, industrial pollution, or any dirty water.

The Basics; the Owasco Lake Inlet, Owasco Lake, and the Owasco Lake Outlet.

There are three phrases that will be used throughout this article. 1) Owasco Lake, 2) the Owasco Lake Inlet (the Inlet), and 3) the Owasco Lake Outlet (the Outlet). The use of Owasco Outlet, Owasco Lake Outlet, or Owasco River has shifted through the years. Currently it is called the Owasco River, although in many months, you can easily walk across it. I will use the old Outlet name here, and instead of the repeated use of Owasco Outlet, I will simply call it the Outlet.

Owasco Lake is the smallest of the six large Finger Lakes being about eleven miles in length and like all the Finger Lakes, it is oriented north to south with the flow being to the north. Although Owasco Lake is the sixth in size of the eleven lakes, it has the second largest watershed that covers 208 square miles.

The Inlet is a 24-mile-long stream that begins in Tompkins County and flows north through the villages of Groton and Moravia, and the hamlet of Locke, before reaching the southern end of Owasco Lake. The Inlet is the major source of water for the lake. Dutch Hollow Brook is the second largest source with a watershed that covers much of the land between Owasco and Skaneateles lakes. There are many other smaller tributaries located around the lake.

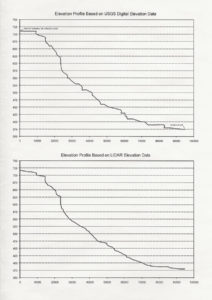

The Outlet is a 14-mile-long stream that flows out of the north end of Owasco Lake. It passes through the city of Auburn, the hamlet of Throopsville and the village of Port Byron, before it’s confluence with the Seneca River at what is called Mosquito Point. The total elevation change along the Outlet is around 325 feet, with 110 feet of fall in Auburn and another 130 feet between Throopsville and Port Byron. The rest of the elevation change takes place along the rest of the route.

This rapid elevation change and the narrow valley it flowed through made it a great place to build dams and mills. In all there were ten (maybe eleven) dams in the city, two in Throopsville and another three in Port Byron.

Owasco Lake level has been controlled in some manner since 1838 when the first dam was built. This dam was in the Outlet about a mile north of the lake located very close to the current “State Dam” can be found. (I place state dam in quotes as it is now owned by the City of Auburn, but has retained the name.) However historically, the Outlet was very shallow and this prevented water from flowing during the drier months of the year. In 1852 the State made improvements by clearing the Outlet and cutting through the natural sandbar that forms at the north end of the lake. The reason that the State was interested was the need of water at the State Prison which used the Outlet water for power, drinking and waste removal. In 1857 the State assumed ownership of the dam and was given the authority to raise the lake level as needed in order to supply water to the Erie Canal at Port Byron. The State rebuilt the dam in 1874. (The State was facing issues with the new enlarged Erie Canal that consumed about three times the water of the original canal. The section of canal between Jordan and Montezuma depended almost entirely on Skaneateles Lake, which could not supply all that was needed. Around 1857 the State began to use the old Beach Mill race that took water from the Outlet near Haydenville and shunted it two miles to the canal at Port Byron.)

We get a sense of the original level of the lake by the number of times it has been increased over the years. Between 1868 and 1872, the height of the dam was increased by 4 feet. In 1880 the lake was at 707 feet above sea-level, and this means that it was once at 703. Today (2022) the summer water level is set at 713, meaning that over the decades, the lake has come up by about 10 feet. (Although there is likely some surveying adjustments made to the datum over the years.) But it is still quite an increase.

Auburn

As the headline states, Auburn was the source of the pollution, so that is where we shall begin.

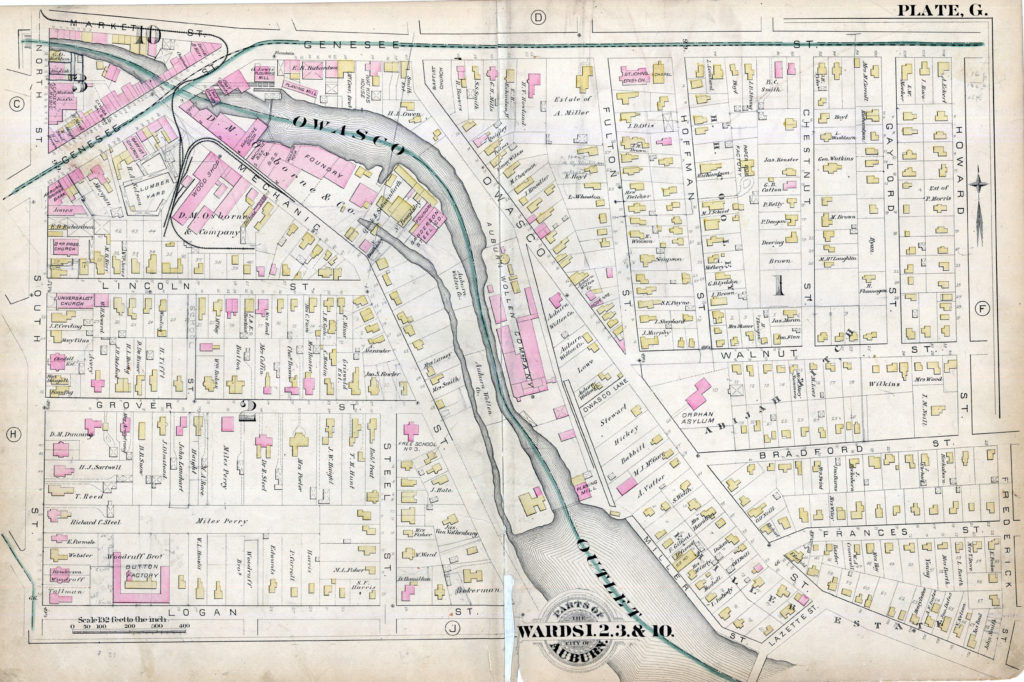

At first, the city residents relied on wells for drinking water and most likely the Owasco Outlet. As the city grew, two things happened. Industry was built along the Outlet to make use of the flowing water to power mills and in the manufacturing of goods. And as the city grew, the sewage wastes of the citizens had to be removed and since the Outlet was the lowest point in the city, it naturally became the city’s sewer.

With the Outlet becoming increasingly polluted, the businessmen of the city organized the Auburn Water Works in 1864 as a private company. They placed the intake and pump house for the water works near the State Dam. As the demand of water exceeded the natural flow of the Outlet, the intake pipe was moved to the lake in 1883. After the 1891 typhoid outbreak, the City of Auburn purchased the water works company in 1894. The City moved the intake further out into the natural deep water of the lake in 1907. The City began to chlorinate the water in 1913 and then built a sand filtration plant in 1916-1917. The City created a dedicated water department in 1921.

A defining moment was the 1891 typhoid fever outbreak that hit the west side of the city hard. The outbreak was located on Division, West, Barber and Derby streets, which is just downstream of the prison. The city fathers first placed the blame on the private run water company. Their reasoning was that the water company had control over the State Dam and could either allow water to flow or to hold it back. As there was no water flowing down the stream, the blame was placed onto the water company. The City made a complaint to the State Health Board and asked for an investigation immediately. The investigators showed up a month later due to a large number of cases across the state.

The investigation team was taken to the State Dam and the water company’s pump house, where they found that the lake was so low due to a drought, that no water was flowing down the Outlet. The water company was free of blame. By this time the water intake had been moved to the lake, so no water in the Outlet was not an issue for the water supply. So where was the fever coming from?

In 1880, scientists established the connection between human feces and water-borne diseases like cholera and typhoid fever. So when they could not point to the flow through the Outlet as the source, the health officers thought they knew directly where to look for the cause. It was the source of the water, the lake!

The team was taken for a boat tour of the lake and along the way they counted cottages and houses. Cottages were the summer only camps, where houses were for year around use. On the east shore they found 64 cottages and 5 houses. They saw that all the sewage and dirty water from these buildings went directly into the lake. At Cascades on the southern end of the lake, the team went ashore and traveled to Moravia where they found that the Inlet was basically the sewer for Moravia, Locke, and Groton. The team resumed the boat tour along the west side of the lake where they found 104 cottages and 5 houses. At the Ensenore Glen House, they found that one of the privies was located directly over the small stream that flowed into the lake. The drought had dried up the stream so that a nice pile of human waste sat waiting for the next rain to carry it away. In all, the team estimated that the waste of 20,000 people was flowing into the Owasco Lake each year, and mostly during the summer. An interesting fact was that the passenger trains that ran along the west bank of the lake all had privies that were simply open holes to the tracks below. (There used to be signs in the privies not to use them when the trail was standing still at the station as all that poop would be deposited in front of the passenger platform.) So any traveler who might be riding the train and passing by and was sick with typhoid could use the toilet and as soon as it rained, that contamination would be in the lake.

The investigation team then inspected what was called the Nye Pond (created by the Nye Dam on the Outlet), and the fever area of the city. The Outlet was, “in a condition much worse than anticipated. The stench from the pond was something awful and although the shades of night were fast approaching one could see festering the mass of filth along the shores of the dam, uncovered by water and emitting a most offensive odor.”

In 1892, a Board of Health issued a report and noted; “By reason of the water in said lake being held back as aforesaid very little water flows down the outlet and through the city, so that the sewage discharged and deposited by the many sewers in said city into said outlet is not carried off, but is left exposed to the action of the sun and air in the very center of the city, forming large ponds of decaying animal and vegetable matter and covering the banks of said stream along its entire length within the limits of the city with sewage from which noxious, foul, offensive and deadly gases and odors arise, contaminating the air and breeding disease and death, endangering the lives and health of the people living along the banks and in the vicinity of said outlet.”

Here is the results of water samples taken during the 1891 tour. They were measuring the average number of bacteria in one cubic centimeter of water.

Mill pond above Moravia…..68

Creek below Moravia …..3750

Owasco Inlet near lake….205

Owasco Lake near south end …14

Owasco Lake near water works intake …11

Owasco Inlet below Auburn…..27,741

These are interesting results and seems to suggest that the drinking water was not the source of the outbreak. However it was pointed out that these samples were taken in the fall after the summer camp residents had left, so the bacteria counts would naturally be lower. And yet it was concluded that the cause of the outbreak was the Outlet itself, not the drinking water.

There was a theory that time and distance would purify any dirty water, so as the reasoning went, any polluted water from the Inlet would be clean by the time it traveled the ten miles to Auburn’s intake. The issue (flaw) with this idea, as it was later discussed in a 1914 article in The Water Chronicle, was that the sewage from the Inlet would collect in the winter ice and then be flushed downstream in the spring thaw at once. And it was realized that some of this ice could float halfway down the lake before melting. This spring time rush of effluents into the lake, at the same time that the summer camps were being opened and occupied, would quickly overwhelm any natural purification or dilution that might take place. And, any ice cut from the lake or stream for cooling purposes from the lake could harbor disease long into the summer months. (Before refrigeration, ice was cut from lakes, ponds, and deep pools in streams, and then stored in ice-houses. Sawdust would be placed between the layers as this would serve as insulation. Ice could be stored well into the summer in this manner.) In any case the water of the lake was likely the cause of the typhoid outbreaks. (author’s opinion)

Although the 1891 typhoid outbreak outlined a number of issues, it was not the first time that the condition of the Outlet had been noted. In 1887, John Hayden of the Haydenville Hayden’s, sued the city over the contamination of the outlet and that the city was directly responsible since they dumped all the waste into the Outlet. The pollution would soil the cloth that was turned out by the Hayden Mill. The city attorney responded that the city had every right to use the Outlet to drain away surface water and that state law was not clear about the dumping of sewers, however that as a rule, “a running stream would purify itself off all impurities within a distance of ten miles.” The Hayden case was never settled and as the Auburn Daily Bulletin noted in 1891, “hangs fire somewhere in the mysterious realm of red tape.” Oddly, in the same article, the Bulletin extended it’s sympathy to Port Byron, who they noted, “should have been built just south of Moravia.”

Science would win out over typhoid and other diseases as in 1908, Jersey City became the first American municipality to install a chlorination plant to treat their water. Soon most cities began to follow suit. Auburn had been treating their water with with some chemicals in the early 1900s and installed a chlorine system in 1913. The sand-bed filtration system was installed in 1920 and these measures afforded the city residents a high level of protection.

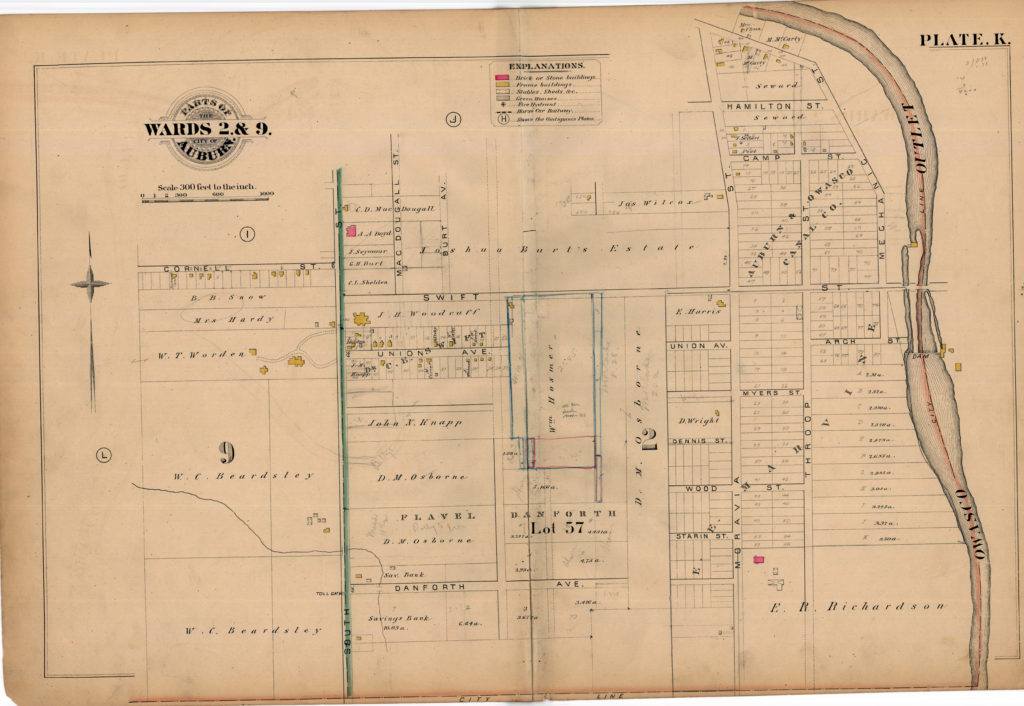

However, as the city’s water was made safe, Auburn’s sewage remained a menace. The city did build three “treatment plants.” An article by Frank Carr in the November 21, 1933, Citizen Advertiser outlined the city’s sewers. Wards 1,6, and 10 drained to a small treatment plant located on Hunter Brook. (If you are not familiar with Hunter Brook, it is North Brook today. The headwaters for this begin small stream begin near the large Dickman Farms nursery flows into the pond at Hoopes Park, and then north to the Erie Canal between Port Byron and Weedsport.) Wards 4,5,6, and 7 all flowed directly into the Outlet as did all the sewage from the Prison. What was called Ward 9 flowed into Crane Brook on the west side of the city, although it was pointed out that the “real” Ward 9 also flowed into the Outlet. In 1935, it was reported that Auburn had 33 sewers, or about 75% of the city, draining into the Outlet. The rest of the sewer system was so old that it was obsolete.

So, to wrap this up (and there is a lot more!) the Outlet served as Auburn’s sewer and in dry years, more sewage ran down the stream then water. And when it did flow, the water simply washed away the accumulated sewage, which all flowed downhill toward Port Byron. So let’s go there.

Port Byron

In Port Byron, the residents had two sources of water. The first was the private hand-dug wells that dotted the village. The second source was the Owasco Lake Outlet. Like Auburn, the early village residents settled around the banks of the stream to make use of the water power for mills and manufacturing, and of course, to drink and cook with. In those early years, the waters flowed clean, but as Auburn grew, the water was less safe to use.

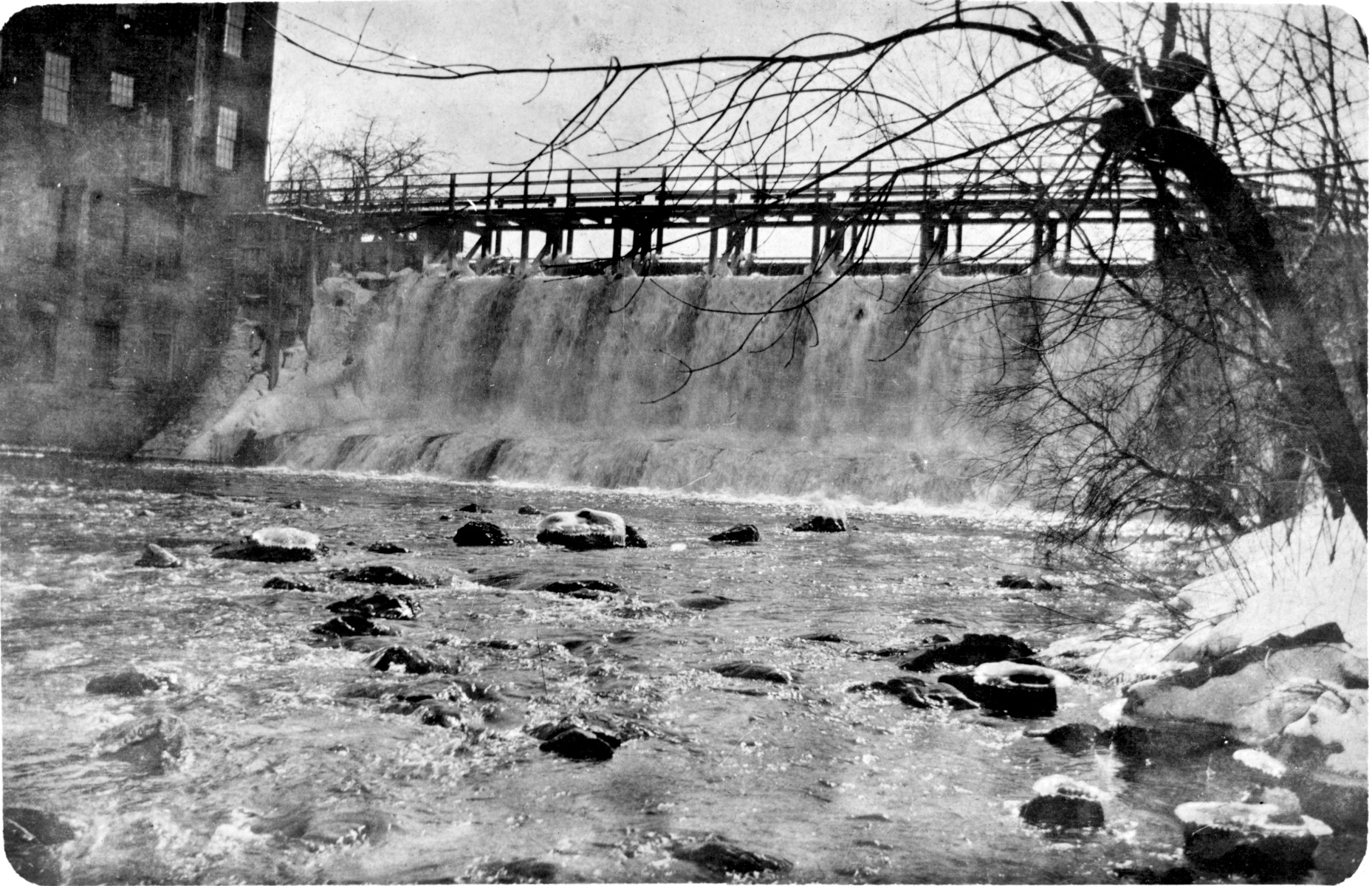

In 1865 (this might be 1875, sources give both dates), the village constructed a water system mostly for fighting fires. Fires were a major issue for any village or city with all the heat and light coming directly from open flames. This system was piped to about 65% of all the villages homes and businesses. This water system was fairly basic. A pump house was built on the mill dam just upstream from today’s Mill Street. The water was pumped directly into the mains or to a small open reservoir located up on Halsey Road. Just as today, the height of the reservoir and gravity provided the pressure to the fire hydrants. This system greatly aided the local firemen in their battles to save homes and businesses.

This millpond is the one we see in lots of postcards. It was likely built around 1820 to supply water to the early mills of the village and was in use up through the 1970s. Over the years many industries had made use of the millpond, grist mills, plaster mills, foundries, wheel-rights, cheese factories and tanneries.

By their very nature, any pool of water, pond or even lake, will begin to fill up with organic debris, natural sediments, and any other wastes that flow down the stream. The faster moving water will carry heavier particles and when they hit the slow water in the pond, they settle. If they were not cleaned out the ponds will begin to fill, become marshes, and then disappear. In 1915 the State Board of Health noted; “The mill pond from which the water is obtained was full of sediment and sludge at the time of the inspection. Considerable scum was also seen floating in the water and the sludge deposited on the bed of the pond was in an extremely putrefactive condition as evidenced by the large number of gas bubbles rising to the surface. The larger part of the pond has become filled with this sludge and sediment, and on this filled portion, cat-tails and flag have grown.”

The intake for the village water system was located in this organic morass. If it was only used to fight fires, there would not be an issue. However, as indoor plumbing came into vogue and common use, people began to tap into this system to supply their households with water for bathing, watering the garden or animals, or flushing the water closet (toilet). People were advised not to use this water as potable water (for drinking and cooking), but any visitor the village would not realize this.

The 1915 report that led to the headlines in the paper were not the first time the issue had been raised. In 1897, Weedsport’s Cayuga Chief published an article titled, “Pure Vs. Impure Water” in which they touted Weedsport’s pure clean well water, while Port Byron had a had “a water supply seldom equaled for its filth,” and that “it had washed into it the excreta of 32,000 people and filth of every name and nature.” In 1903 the State had issued a report outlining the amount of pollution in the Outlet and laying the blame squarely on the city of Auburn. It was said that these conditions were a hazard not only to Port Byron, but to other downstream cities such as Phoenix and Oswego.

So in short, it was well known that Port Byron was using Auburn’s sewage as a water source. The village health officer was Dr. Daniel Gilbert and he freely spoke about the dangers that village faced from the dirty and polluted water. Dr. Gilbert was the one who called in the state board of health and helped to investigate the village water supplies. In 1916 he gave an interview to an Auburn newspaper where he directly said that the death of the Rev. George Pearsall was from typhoid caught from the sewage filled water in the Outlet. He must have been frustrated at the slow reaction by the village fathers as he said that he had no idea of what they were planning to do.

The state of the village sewage disposal wasn’t much better then what Auburn used. It was all cesspools, chamber pots dumped into open ditches, the Outlet, and in some areas, the Erie Canal. Those who were near the Outlet simply returned their dirtier water to the stream, and those who lived near the canal could flush their troubles away to Montezuma.

The Erie Canal is an interesting point as it sat higher in the landscape, it had a higher potential to contaminate nearby wells. The canal was well known to be used as a open sewer for the villages and cities it passed through. Luckily the water that passed through Port Byron came from Skaneateles Lake, but only after the villages of Skaneateles, Elbridge, Jordan, and Weedsport had made their contributions. (All the canal water emptied into the Seneca River at Montezuma, where it would eventually mix with the water from the Owasco Outlet and all would then head off toward Baldwinsville, Phoenix and Oswego.)

So…

To circle back to the village water supply, as more homes got indoor plumbing and more water was then used by the residents, it all flowed out of the cesspools and ditches into the nearby wells. To be blunt, Port Byron was not only drinking Auburn’s sewage, it was drinking its own. This all led to the 1915 headlines that no source of water was safe. As shocking as this might have been, it wasn’t enough to spur the village fathers to action. Each year the State Health Board would note that Port Byron’s water supply was unfit and that little was being done about it. In 1933 the Chamber of Commerce demanded that something be done about the sewage in the Outlet and this was followed by the Sportsmen Association and the County’s Board of Supervisors in 1934.

It would be the Great Depression, and I suspect a new school, that would change things. In 1930, plans were made for a new water supply and the Chronicle noted that the City of Auburn was finally ready to co-operate. Five years later in 1935 plans for a new water line between Auburn and Port Byron were presented. Two years later in January 1937, the work began as a Public Works Administration project which were designed to put people to work. The water line was completed by December. It likely is not a coincidence that the new water line and new centralized school were built at the same time. As part of the project all the water lines were flushed and decontaminated, and the open reservoir was replaced with a water tank.

About the same time, the PWA was funding a improved sewer system for Auburn. All the sewers in the city were incorporated into a intercepting sewer system that treated the sewage and then dumped the clean(er) water into the Outlet. I say cleaner as in 1953 it was reported that in the drier months, the local paper estimated that half the flow of through the Outlet was raw sewage.

It would take another 30 years before Port Byron would get it’s own sewage treatment system. Under the Pure Waters Act, all villages were required to install sewage treatment plants and Port Byron got its own plant in 1967.

And… The Dams

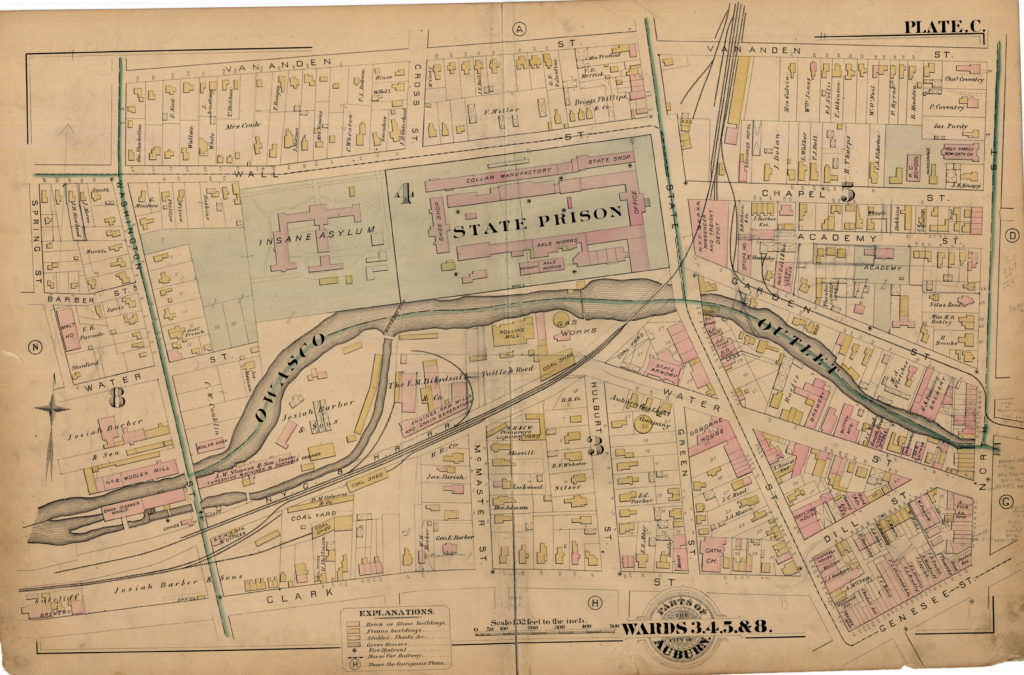

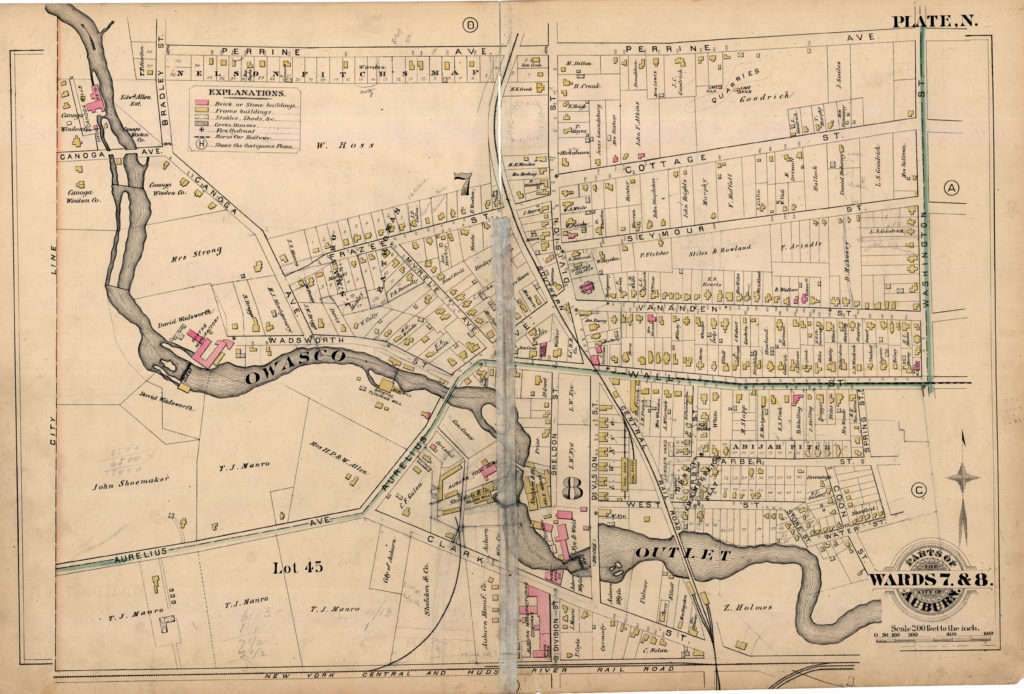

This is simply for the dam geeks as there are times that the subject of the dams along the Owasco Outlet come up in discussion. The 1882 map of Auburn is the best source as all the dams were in operation and with this I have found two decent lists of these dams. The first is from an 1983 Citizen article and the second is from Hall’s History of Auburn. So I will list both with the dam height. They were, from south to north;

State Dam 13 ft – State Dam 10 ft (although called the State Dam today, it is owned by Auburn)

Mill Street 26 ft – Big Dam 25 ft (this is today’s Mill Street Dam)

Hardenbergh 13 ft – Hall and Lewis 10 ft

Prison 8 ft – Prison 8 ft

Dunn and McCarthy 27 ft – Barbers 25 ft

Nye and Wait 27 ft – Nye 25 ft (this is today’s North Division Street dam)

Shoe Form 18 ft – Casey 25 ft

Allen 12 ft – Haydens 11 ft

Wadsworth 12 ft – Wadsworth 11 ft

Canoga 9 ft – Halls 20 ft

This first adds up to 165 feet of head in the city, while Hall says that it was 170 feet. Hall also notes another 10 feet of rapids, so the total fall (head) was 180 feet.

Note- A list of sources can be sent to anyone wishing to dig deeper into this study. Simply contact the author.