The construction and opening of the New York State Barge Canal in 1918 ended the canal era in Port Byron. The original Erie Canal had been built through the young village in 1819 and had opened for business in 1820. Ninety-eight years later the old Erie was abandoned, replaced by a new and modern canal that made use of a canalized (dredged) Seneca River, about two miles north of the village. The construction of the new canal had changed the landscape in many ways. It creating islands where none existed before and removing islands that had been used by the Indigenous Peoples for centuries. And when the old canal was drained, a large scar was left across the county that had to be filled in, bridges had to be destroyed, and sanitary sewers that once poured their goodies into the clean canal waters had to now find new outlets.

For a brief time, there was talk about transforming the landscape of the village in a much different fashion. As the work on the new Barge Canal was completed, the State began to look into the idea that the city of Auburn should have it’s own connection to the new canal. This new canal would have passed directly through the middle of Port Byron.

This proposal wasn’t such a radical idea as the notion of building a canal that would connect Auburn to the Erie Canal had been kicked around since 1830. My suspicion is that John Beach’s two-mile-long millrace that snakes it’s way up the valley was built with the goal of becoming part of this canal spur. Work began on the Auburn and Owasco Canal in 1835, and a short section was constructed in the city before the funds ran out and the excitement turned to the new railroads. So in 1917 the idea of a canal to Auburn wasn’t new, it was ninety years overdue.

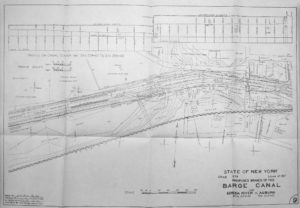

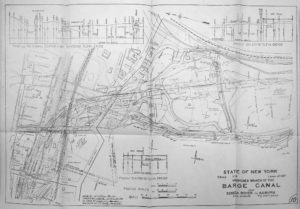

The proposed route of the new canal would have begun near Montezuma. Why Montezuma? The proposed canal was laid out to avoid conflict with the three railroad lines that passed north of the village. The state had just forced these companies to build numerous bridges to accommodate the route of the new canal between Albany and Buffalo, so to avoid further battles, it was easier to take a slightly longer route to the Seneca River. Crane Brook was to be dredged up to the line of the old canal. Lock 1 was to be located along this section. From there the new canal would follow the old canal up to Port Byron, passing right through Old Lock 52. Just to the east of River Street the canal would turn south into the valley of the Outlet, and Lock 2 was to be built just behind St. John’s Church. Lock 3 was to be just south of Hayden Road, and Locks 4 and 5 were to be about a half-mile south of Lock 3, deep in the valley. These were to be tandem locks (like we see in Seneca Falls) with a combined lift of 60 feet. Lock 6 was to be near Throopsville and Lock 7 was south of that. The canal spur ended just north of Canoga Road and west of Bradley Street, about where the City Landfill is located today. There was no plan to take the new canal through the city to the lake as there was no industry on the lake to warrant the cost of the extra locks and digging that would be needed.

![]()

Each lock would have had a dam to back up the stream and create at 12-foot deep navigation pool for the barges. At each dam it was proposed to add the necessary equipment to produce electricity. This would have been quite the bonus for the local residents who were just getting their first taste of living in an electrified world.

The canal spur was proposed to carry 500,000 tons of goods a year. To compare this, the new cross-state Barge Canal was built to carry 20 million tons a year. This would involve a number of lockages each day that would use up hundreds of thousands of gallons of water. To supply the canal with water, as well as keep the lake as a public supply of water to the city, it was proposed to raise the level of Owasco Lake by about four feet. The total cost of the canal was estimated to be $8.8 million with another $400,000 for work on the dam that would have been modified to accommodate the needed lake level.

The Auburn Citizen, Page10, 1922-04-29

Once the planning was complete, the arguing started with some saying it was a giant waste and others saying it was needed for progress. Unfortunately the fight for the canal lasted up through 1922. By this time, many in the state started to see that the promises of the Barge Canal did not live up to reality. No canal spur would be built.