Note- This is a longer version of the January 31 2021 Citizen article.

Over the last few months my life has become somewhat preoccupied in making connections and additions to the Port Byron Family Tree project. I have found it to be a great distraction from all the news and frankly a great way to avoid any work. As I don’t have any family in the area each new name becomes an exciting way to spend hours of research, so much that on occasion when she wishes to see if I am still breathing, my wife will wander into the study and say, “who now?” To start my digital journey, I will simply start with a search word such as “canal” or “boat”, and see what comes up. This random type of search works in the Lock 52 HS digital archives as we only have papers from Port Byron. If I tried to do this on a larger site, I would be overwhelmed with hits.

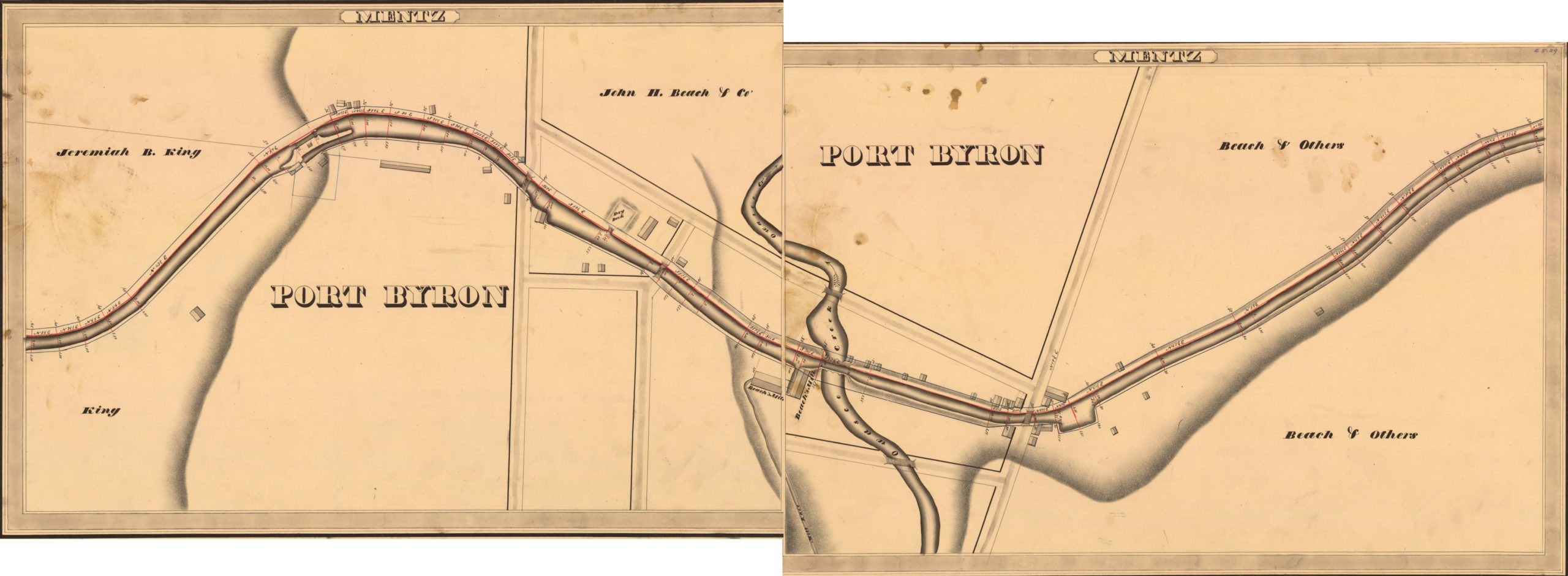

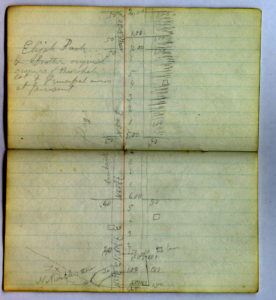

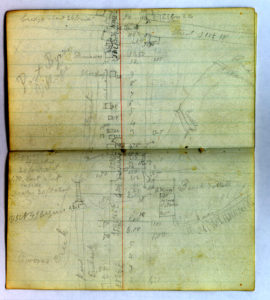

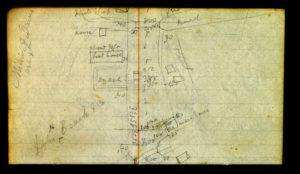

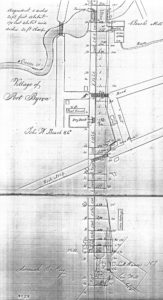

One of the responses that peaked my interest was a village business directory from the 1845 Port Byron Herald where I found a listing of fifty-one village businesses, a mix of thirteen groceries, three tailor shops, four blacksmiths, two wagon makers, five attorneys, three physicians, and more. I found this so interesting as we know so little of the village in this period of time. There are no photographs to help us visualize the village, and few writings to describe it. One of the artifacts we have of the period is Holmes Hutchinson’s 1834 map of the canal which shows us how buildings were built along the canal and helps to explain why our village streets are laid out as they are. However as the focus was the canal, this map doesn’t not show us most of the buildings and streets of the period, for instance the Eagle Tavern or even Pine Street. (However, however, the surveyor’s field notes do help to fill in a few of the details.)

When the Herald published the directory in 1845 the canal had been in use across the state for twenty years. Although the state was in the process of rebuilding the Erie Canal to larger dimensions, the canal that passed through the village would have looked as it did from its opening in 1820. And aside from a wagon on the roads, the canal still the only way to ship goods across the state. If you have a great-grandparent who was in the village in the 1840s, they would have been able to stand on one of the bridges over the canal and watch as boat after boat filled with cargo passed under their feet, maybe even exchanging a few words with the captain or his wife, or even a relative who worked on the boats. Mixed in with the slower cargo boats, they might have watched the passenger carrying packet boats whisk along at four-miles-per-hour, perhaps not realizing that in less then a decade, all those passengers would be passing by to the north on new trains at ten times the speed.

The newspaper directory tells us that if your grandparent took a walk along the towpath, they would have passed by the stores of Alanson Whitcomb, William Hinman, and John Campbell, all who sold groceries to the canallers. They might have heard the toot of the tin horn as boat captains let the lock tender know of their approach. They may have heard the low rumble of the turning wooden wheel and gears at Beach’s Mill as the millers and hired laborers worked at taking in boatloads of wheat, grinding it into flour, and then packing the flour into barrels. To the west, about where our highway superintendent lives, was the boat yard of George Millner, where leaking boats could be repaired and new boats built. And near Ed and Jeans corner the canal widened here into a small basin where the boats could dock, and then discharge or receive cargo from the area. A storehouse at the basin held the goods until they could be loaded or retrieved. If they ventured a bit further to the west, your grandparent would have reached lock 60 and watched as the boats were raised and lowered, and if the folklore is true, maybe a few fisticuffs as the boaters fought for position in the lock queue. They also could have watched as the lock-side sawmill cut lumber into barrel staves for the large cooperage, and then watched as the coopers fashioned the staves into barrels in the long low cooperage.

Of course, this all takes place in the theater of the mind, backed up with a few facts from the 1834 map, the newspapers, and other sources. To dig a bit more into village life, I decided to download the 1850 census into a spreadsheet and then do a bit of sorting. Every genealogist knows that the 1850 Federal census was the first to list each person and if they had one, their occupation. For me, it captures the last days of Port Byron, Mentz and even Montezuma before the New York Central Railroad was built across the state. At that time Montezuma was still a part of Mentz and thus, we get to see all our nice neighbors. Here is what I found.

There are 5235 people listed and of those, 1500 list an occupation. There were ninety Erie Canal boatmen listed, and one boat-woman, although I don’t know if all these men actually lived in the area, or if the census taker was standing at the lock counting everyone who passed. There were five lock-tenders, although I expect that there were more as we had three locks in the town at that time. There were four canal toll collectors at the canal office in Montezuma. There were twenty-three millers, and I do expect that many of them worked at the large Beach Mill. There were twenty-six coopers who turned out the barrels for the mills. The two villages had thirty-six shoemakers, which unless there was a shoemaker convention in town, is a very high number and one I feel reflects the canal. In all, I can figure that about ten percent of the population made their living on or by trade from the canal, and I expect this could be higher if I added in the inn keepers, blacksmiths and others. Seven-hundred-thirty-three of the population were listed as farmers, and this number doesn’t include all the farmer’s wives and children. Many of these people would have been raising their crops to sell by way of the canal. If even half these folks were added to my rough estimates, I think it is safe to say that the work of over thirty percent of the population was in jobs that were directly impacted by the Erie Canal.

Over the coming year I will be digging into the lives of those who worked on the canal or along the canal. While there are a few well know names, hopefully we will meet a few of the not-so-well-known names. It should be fun.