By Anita Messina

The Denmans, Genevieve Mae, her husband Charles and their daughter Cheryl Mae were moving to their new home at the farmstead owned by Charles’ parents, D Lulu and Jesse Denman. The pick-up truck was full to overflow with their possessions. Two-year-old Cheryl Mae stood on the seat anxiously peering through the rear window, scanning the bed of the truck. She kept a vigilant eye on the cargo “to be sure my toys were coming with me.” They reached her grandparents’ farmhouse a short distance from the lane where they had lived. Toys safely in tow. The new household was to be a quiet home. Cheryl’s first stern warning was to play quietly with her toys and make no noise when her grandfather was nearby. She remembers that she seemed to be invisible to him. Her grandfather never spoke a word to her, nor did he as much as glance her way.

Genevieve’s father, William Osburn Jr., grew up in a large brick home on South Street not far from the present Methodist church. It was a grand estate owned by Mary and William Osburn Sr. and always referred to as The Osburn Manor. Of sturdy construction the home still stands where it always was, in use as a residence to this day. Eunice Rooker remembers The Manor as an impressive home and a place known for hosting lavish social gatherings. One newspaper clipping speaks of the Osburns entertaining many guests at the celebration of their 50th wedding anniversary. On that occasion the home, says the newspaper item, was filled with 150 potted plants.

Newspaper archives have evidence of the Osburns and the Denmans being socially responsible and civic-minded families. Sarah (Austin) Osburn, Cheryl Mae’s great-grandmother, in 1824 organized the first Sunday school for the Presbyterian Church. She was also the community historian who kept records of earlier village families. Cheryl Mae, now Cheryl Denman Longyear, has carried on Sarah’s zeal as a spirited community advocate and Montezuma’s historian.

Another equally influential family, Cheryl’s paternal great-grandparents, Adelia and Edward Erity, lived on an impressive farm once located on Mintline Road near the Mentz-Montezuma town line border. Cheryl writes, “E. B. Erity is listed in the ‘History of Cayuga County’ as ‘Dealer of bailed hay and straw and agricultural implements.’” Cheryl adds, “It sounds like Erity and his nephew, Theodore Lyman Brooks, were collaborating on developing the farming industry of the area. I have an article that a spark from the engine on the NYC RR caught Erity’s load of straw on fire on a canal boat burning up the straw, and Erity recovered $910.17. So Erity was in the business of shipping straw on the canal to other ports.”

The nephew, the enigmatic Theodore Lyman Brooks, lived in the Erity home. No accounts of his life are found other than in relation to his life on the Erity farm. We know from United States Patent Office files that three patents were issued to him when he lived there: “Feeding Device for Horses” (1888), “Coin-Controlled Electrical Apparatus” (1891) and “Parcel Receiving and Delivering Device” (1902). He wrote to the Port Byron Chronicle that he “invented, planned, patented and completed a hay, grain and stock barn on the farm of Mrs. E. B. Erity, entirely unlike any building ever constructed by man. It is without beams or braces, mortices, tenons or pins. There isn’t an auger, chisel, chalk line, or scratch mark on the entire barn.” Brooks claimed to have a patent for this barn design , but no patent office record has been found attesting to that.

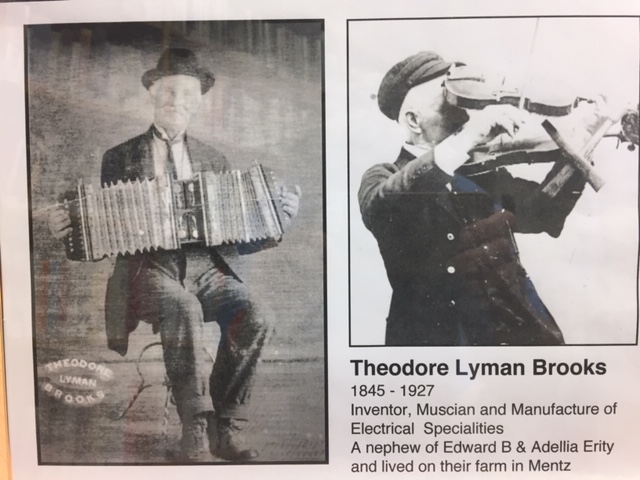

Little else is known of Brooks. A photograph shows him playing a small German accordion, and another shows him playing two violins, braced, so he could use two bows to play them at the same time.

A newspaper article tells us that he could repair a gun, though not without inflicting a wound to himself when he neglected to check for a loaded chamber. Brooks was treated for a bullet wound near his eye.

Although local cemetery files have no record of his burial, the four-sided large head stone for Adelia and Edward Erity in Mt. Pleasant Cemetery bears his name and one word on each side: writer, inventor, publisher, musician. Cheryl mined one other terse comment noting that Brooks was in the county asylum from 1922 until his death in 1927. Was his confinement for mental health or for a physical condition? Those facts are not known. Cheryl’s research found, according to census records, he and several siblings lived with their parents, Henry G. and Julia A. Brooks. Cheryl notes an early map shows the Brooks’ family home was close to the canal a short distance west of the present Erie Canal Heritage Park visitor center. So far no one knows why he came to live on the Erity farm in Mentz. The unanswered questions are, as they say, one of ‘history’s mysteries.’