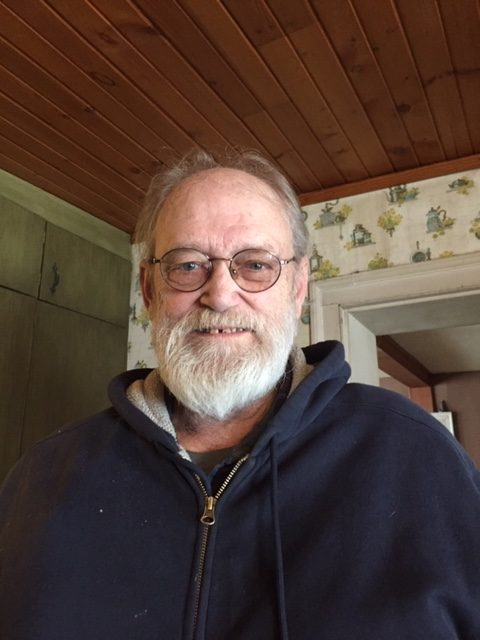

By Anita Messina

John Seamans, nine years old, finished the last of his cold cereal, listening. He listened for a nearby screen door to fling open and slam shut. That was his signal that the first of the Pine Street kids was on his bike and headed for the cemetery for some energetic games of Cops and Robbers, Cowboys and Indians, War! They never once desecrated that cemetery, John said. Never even thought of doing that.

Back then in ’58, ’59. ’60 a kid was free to plan his day. As John says, “There weren’t ‘soccer moms’ when we were growing up.” We were on our own.

The Pine Street moms were home baking cookies and freezing homemade Kool-Aid Popsicle. The boys knew which houses to stop at for sustenance breaks. Mrs. Biss, Mrs. Neal and Mrs. Campanello were three of the moms who kept a tasty inventory of fresh-baked cookies.

When the boys tired of playing their victor-and-vanquished contests, they raced their bikes on the cemetery roads or organized a baseball game at Triangle Park. Whenever a ball was hit long, John would warn, “That has Pratt’s Greenhouse name all over it!” If so, they never ran away from a mishap. They faced up to it. Sometimes they were let off easy. Sometimes it cost them, as it did the day John accused the Neils’ house of ”getting in the way” of one of his long drives. John asked Mrs. Neil how much it would cost to repair the shattered window. Apparently Mrs. Neil had enough experiences with broken panes to answer quickly, $7. John told her he’d be right back, then he high-tailed it home to get his bail money.

Pine Street Park was just a small triangle, John said, “but we were small so it was big enough for us.” Sometimes we’d bounce balls off the Scout House. The building was once a church built in 1822. The church proper was built on stilts and was open at the bottom so that horse-drawn wagons could drive under and stay dry in bad weather. When it was closed in, it made a good backstop for balls.

John made little mention of girls being part of the summer games. He said, “Sixty-five years ago girls played girl things. Boys played boy things. But nobody had any issues if girls were good enough to play ball. If they were good enough, they played.”

It seemed no one started any trouble. Or not much anyway. Once in a while Dukey Devall would pick on a little kid, and once Mary Ann Neal threw a stone at John, hitting him hard enough in the temple so the bleeding made a scary impression. He played dead, and, suspecting herself of murder, Mary Ann ran into the house and hid under the kitchen table. What possessed her to throw a stone? “She probably ran out of walnuts,” John said.

When they needed a break from roughhousing, the boys visited Roma Jetty on South Street. Roma was confined to a transport chair, “wheelchair” it was called in those days; and she was always happy to have company, especially company who knew how to play Canasta.

The boys didn’t need much money to maintain their lifestyle. They needed to keep a cash reserve for when those windows “got in the way.” And now and then they’d need a coin or two to buy a baseball card or a sundae at Lucy’s. Lucy’s was the popular ice cream parlor across from the former Shoppers Guide. Lucy served really good ice cream, John says, but he singles out the sundae dripping with chocolate sauce and sprinkled with nuts. Lucy always served a glass of ice water alongside. John said that ice water always tasted so good.

No sir, they didn’t run home begging a handout. They earned their spending money catching suckers in the outlet and selling them to the migrant farm workers who lived in the small houses behind the wash house near Emerson’s Food Land. That was where the Dollar Store now stands. They didn’t get much for the suckers. Their big ticket iten was snapping turtle. The workers paid $5 apiece for those gourmet treats.

So that’s how they spent summers. They were outside all day and sometimes all night too. John, his older brother Glen and his little brother Ramon lugged sleeping bags up Pine Street Hill and there slept away the cool quiet night.

The only other evening entertainment was an occasional movie. Two, in particular, were memorable. In the Weedsport movie house he saw “The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad,” (1958). That movie was a particular thrill to see because it pioneered the innovative technique of filming live actors with animated characters. Later when visiting his aunt in Penn Yan she treated John and his brothers to the movie that struck fear in their young hearts–Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Birds,” the 1963 thriller about a huge murder of crows that attacked school children in a small California town. John said on their way home they cowered before every corner, wall, and hedge fearing the sudden wing flaps of crows ready to attack and peck their scalps bloody. “It was scary walking home in the dark after that movie,” he said.

Nowadays on spring mornings John doesn’t linger over breakfast listening for screen door reveille. Rather, he raises his nose and sniffs. When he smells the rich loam of freshly turned farmland, he’s out clod hopping and searching for the fresh crop of arrowheads that has been turned over by the plow blade. He reveres the Algonquin and Cayuga hunters who left the knapped flint in Port Byron, and he honors each sharply pointed stone. John has an impressive collection, all sizes down to the tiniest bird-killing missile, no bigger than a thumbnail. He picks up even the smallest fragment of flinted stone, carting home each tiny shard. “I pick up every little piece,” he says, “so I won’t have to stoop to look it over again next year. At my age,” he says, “I don’t have many bend-overs left.”