For those family genealogists out there, the term “brick wall” has a certain meaning. It is when all the clues run out and those exciting new discoveries come slowly or not at all. Well those “brick walls” can also pop up in the study of general history when we can’t find answers to our questions about a subject or topic.

I recently received a question about a family of coopers who were part of Port Byron’s very active barrel manufacturing business. And I had to say that what we don’t know outweighs what we do know. Most of what is known comes from a short description in the Brigham’s 1863 County Directory, where a short sentence says that the cooperage was in a two-hundred-foot-long stone building and that it supplied barrels to the large mill of John Beach. It has been written that this mill could turn out 500 barrels of flour in one day, so it is no surprise that coopers were in high demand. The Beach cooperage employed about 50 men.

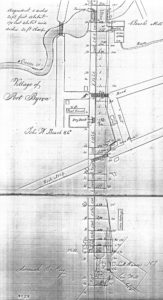

Further clues were found in an 1834 Erie Canal survey that noted the location of the cooperage. (This map is a bit misleading as it shows the canal running straight down the middle of the page, but that is how surveys were done.) At the bottom of the map you will see old lock 7 (The seventh lock west of Rome. This would later be renumbered as Lock 60.) Next to the lock there was a saw mill which used the excess water flowing through the canal to power the saws. Above the lock you can see the “stone cooperage.” It is likely that the sawmill supplied staves to the nearby cooperage.

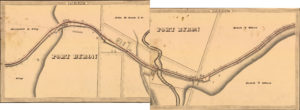

Here is the final map showing the actual route of the canal. The lock, saw mill and cooperage are on the left side above the Port Byron label. Beach’s Mill is where the two pages were joined together. Note that the cooperage isn’t labeled on the final map, only the survey.

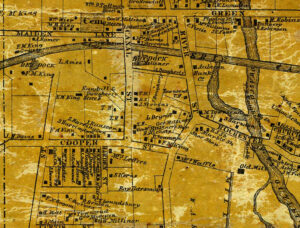

This third map was from the proposed enlargement of the Erie Canal when the locks were doubled in the 1850s. You can see the new lock 52 and the old lock 60 just below them. The cooperage was also noted as a long rectangle in the lower right side of the page.

Our last clue is from the 1859 map where we find Cooper Street, what is today’s Rochester Street west the Outlet. So although this was quite a large concern, that is all we know right now. Note the alignment of Rochester Street running over to River St. This is now Moore Place.

The 1850 census notes that there were 27 men who were coopers, but these were likely the last of the industry as by 1850 there is no mention of the cooperage in any history. The reconstruction of the Erie Canal in the 1850s likely wiped out any trace of the stone building as it doesn’t appear on the 1859 village map. The family of coopers that prompted the question moved on by 1855.

As happens so many times with local history, the description of the business that was printed in 1863 was repeated word for word in later historical accounts. Even the local paper, normally a wealth of local information, never mentions the seemingly long forgotten business. An article about a house fire in 1914 notes that Samuel Dougherty was the foreman of the Beach Cooperage, but that is it. His son, Henry Dougherty of mincemeat fame, operated another cooperage later in the 1800s, maybe suggesting that he or his father had carried on the business in some fashion. The Dougherty cooperage was located on the west bank of the Outlet between what is today Rochester Street and Moore Place.

John Beach’s mill, once called the largest in the state, is also another of our “brick walls,” for it predated photography and no one cared to make a drawing of it. So again, all we have are the often repeated historical descriptions of a business that saw it’s prime days in the 1830s. The mill burned in 1857 leaving no trace aside from the two-mile-long mill race that was later used to supply water to the canal. I have written about John Beach and his mill in other articles, so I will let you search them out if you are interested.